Brainstorming Research Questions as a Clinical Researcher

Tehreem Zahid

Tehreem ZahidHow Dr. Tehreem Zahid Brainstorms Research Questions

As a senior clinical researcher and public health student who has worked across several, international and industry-sponsored clinical trials, I regularly read clinical research studies of all kinds.

The fact that I am familiar with state-of-the-art research in my field helps me a lot when I have to brainstorm research questions.

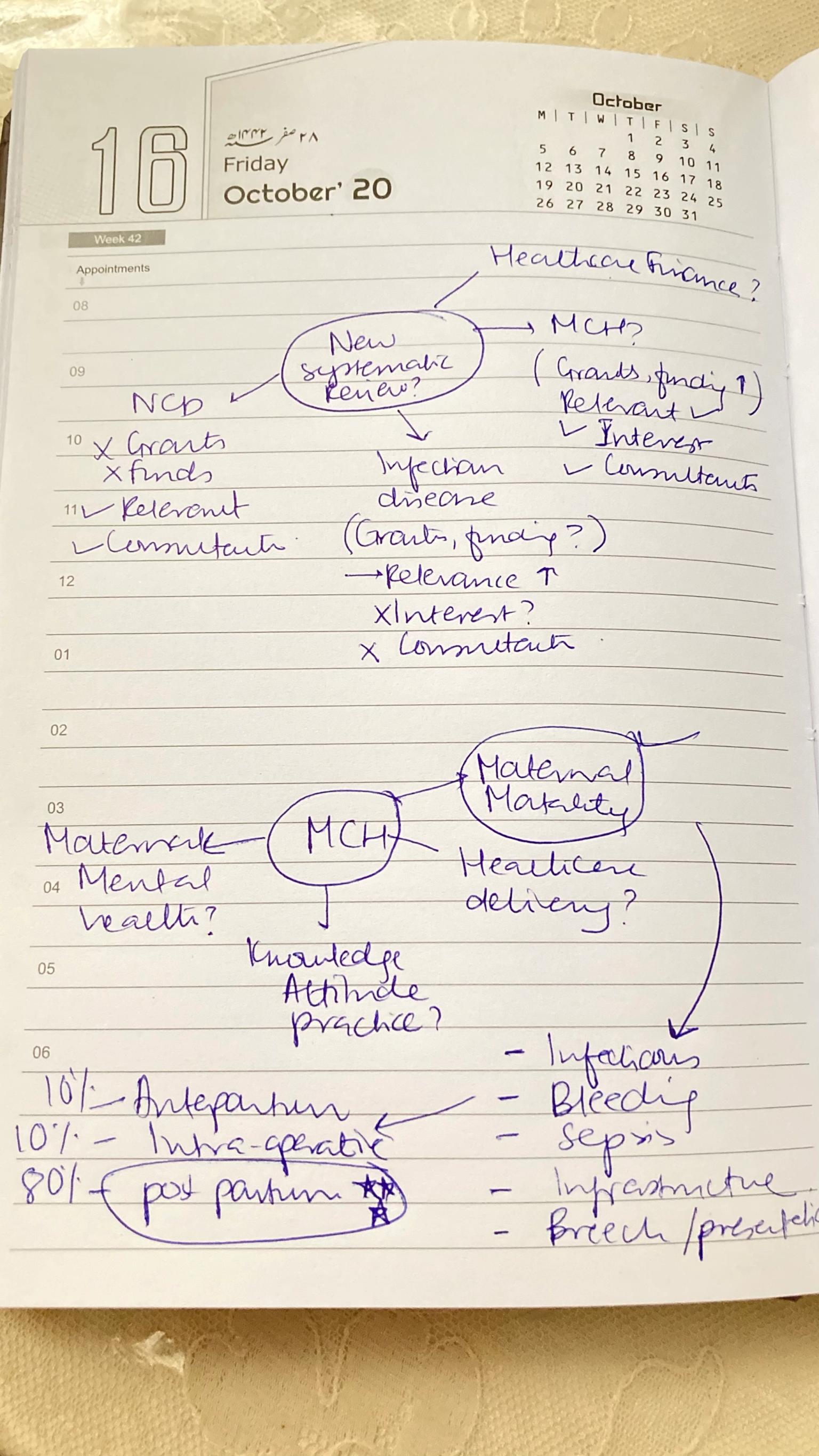

When I brainstorm research questions, I start by building a mind map in a notebook. The good old paper and pen work best for me. You can also do this in an MS Word file.

I start brainstorming by thinking about a theme in a larger field of interest (for example, infectious disease, non-communicable disease, maternal-child health).

Once I have decided upon a theme, I move on to sub-themes. This includes all the relevant ideas and derivatives from the main theme. I jot all of them down.

If you are struggling at this stage, consider getting help from colleagues or friends working in related fields. This will help you answer a very important question: what does the research community want to know?

My current project is a systematic review that focuses on maternal-child health, which involves the well-being of pregnant women and their unborn child.

I started by asking my sister and my best friend (both of whom work in intensive care units) what factors impacted maternal mortality the most in their hospital. They gave me a list of 4-5 main reasons.

Once I had a list specific topics and questions, I looked up relevant literature on PubMed. Depending on your field you can also use Google Scholar. This is the stage that takes most of your time.

The sheer volume of medical literature out there can be overwhelming. Try looking up relevant literature over the course of several days. This will help you figure out what your inclinations are. Note them all down.

Due to my experience in study design, I was able to get a basic idea of what I wanted to work on after a few hours of literature review. In this case, I decided on post-partum hemorrhage (a kind of bleeding that a pregnant woman experiences after delivery).

Once you have the broad topic in mind, the next step is to refine your research objective. Are you interested in demographics? Interventions? Prevention? Reviewing relevant literature will help you answer this question. This is where apps like Connected Papers come in handy.

We may think of our research question as “novel,” but the literature review process humbles you down quickly. A lot of work has already done by people before you.

But sometimes, reviewing literature continually may not work the way you had intended it to. If a continuous literature review results in low yield, it's important you take a break and come back to it after a few days with a fresh set of eyes. This will give you a chance to review your research question from a different perspective.

It is also a good idea that you review the research question with a subject matter expert, in my case it was a consultant obstetrician who sees these patients every day. They may point out technical or logistical issues with your research questions that may arise down the line.

They are especially instrumental when setting the “measurable terms” in your research question as they know if those are clinically relevant.

Cost-effectiveness and feasibility are a major concern in Pakistan; hence it is important to keep in mind the kind of challenges you may encounter during your research.

This whole process may take weeks or a few hours depending on the subject and expertise. It is imperative to focus on niche areas and those relevant to one’s sociodemographic settings.

Remember it is not the number of variables or uniqueness of the question, but how that question will be answered. A seemingly simple question may have a robust study design and statistical power, enough to change practice guidelines.

The question must be broad enough that it captures a wide net of data, which can then help build more hypotheses.

To address the research gaps in one’s field, it is important to read the “limitations” part of the discussion section of relevant papers. See if those research gaps have been addressed in any studies. The methods section is also where you can find research gaps.

If a similar study has been done, you can use a different study design, change the intervention groups, increase/decrease the follow-up period, or increase the sample size.

Go through the results and see what variables have been chosen and what outcomes have been assessed. Both can be modified and refined.

After the research question has been selected, the other parts of your proposal assimilate accordingly. But since research is a continuous and evolving process, one needs to be patient and keep an open mind.

Tehreem Zahid is a medical doctor pursuing a post graduate degree in Public Health. She works as a Senior Clinical Research Associate at the Shifa International Hospital, Pakistan, where she conducts clinical trials, and mentors junior physician researchers. She has collaborated with international research organizations in practice-changing studies published in The New England Journal of Medicine, Annals of Internal Medicine, and Gynaecologic Oncology Reports.